Nitrogen – an exception in the periodic system?

New high-pressure material discovered and a puzzle of the periodic table solved

In the periodic table of elements there is one golden rule for carbon, oxygen, and other light elements. Under high pressures they have similar structures to heavier elements in the same group of elements. Only nitrogen always seemed unwilling to toe the line. However, high-pressure researchers of the University of Bayreuth have actually disproved this special status. Out of nitrogen, they have created a crystalline structure which under normal conditions occurs in black phosphorus and arsenic. The structure contains two-dimensional atomic layers, and is therefore of great interest for high-tech electronics. The scientists have presented this "black nitrogen" in "Physical Review Letters".

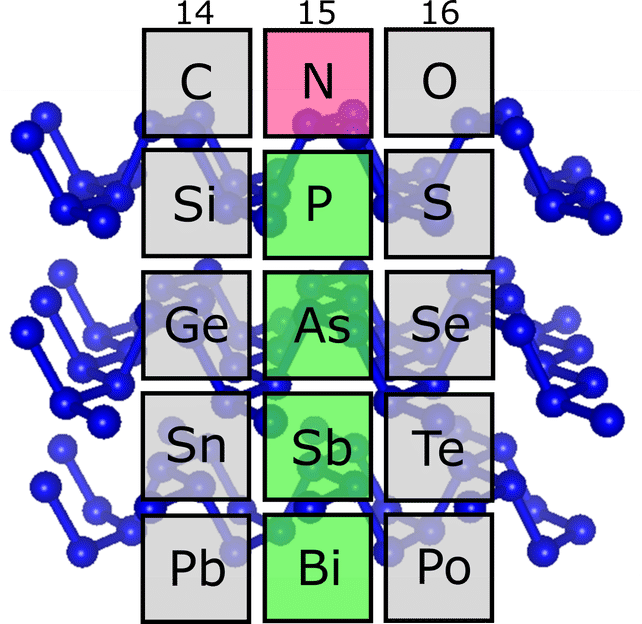

Under extremely high pressures, nitrogen (red), like the heavier elements phosphorus, arsenic, antimony and bismuth (green), has a structure consisting of zigzag-shaped two-dimensional layers.

Dominique Laniel

Nitrogen – an exception in the periodic system?

When you arrange the chemical elements in ascending order according to their number of protons, and look at their properties, it soon becomes obvious that certain properties recur at large intervals ("periods"). The periodic table of elements brings these repetitions into focus. Elements with similar properties are placed one below the other in the same column, and thus form a group of elements. At the top of a column is the element that has the fewest protons and the lowest weight compared to the other group members. Nitrogen heads element group 15, but was previously considered the "black sheep" of the group. The reason: in earlier high-pressure experiments, nitrogen showed no structures similar to those the heavier elements of this group – especially phosphorus, arsenic, and antimony – exhibit under normal conditions. Instead, exactly this kind of similarities could be observed at high pressures in the neighbouring groups headed by carbon and oxygen.

Black nitrogen – a high-pressure material with technologically attractive properties

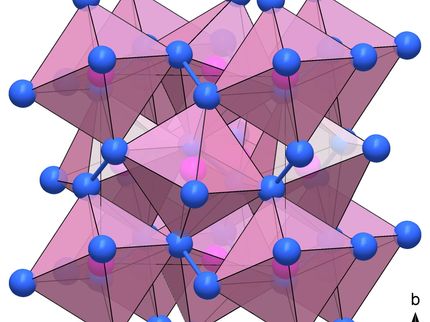

In fact, nitrogen is no exception after all. Researchers at the Bavarian Research Institute of Experimental Geochemistry & Geophysics (BGI) and the Laboratory for Crystallography at the University of Bayreuth have now been able to prove this with the help of a measuring method they recently developed. Under the leadership of Dr. Dominique Laniel, they have made an unusual discovery. At very high pressures and temperatures, nitrogen atoms form a crystalline structure that is characteristic of black phosphorus, which is a particular variant of phosphorus. It also occurs in arsenic and antimony. This structure is composed of two-dimensional layers in which nitrogen atoms are cross-linked in a uniform zigzag pattern. In terms of their conductive properties, these 2D layers are similar to graphene, which shows great promise as a material for high-tech applications. Therefore, black phosphorus is currently being studied for its potential as a material for highly efficient transistors, semiconductors, and other electronic components in the future.

The Bayreuth researchers are proposing an analogous name for the allotrope of nitrogen they have discovered: black nitrogen. Some technologically attractive properties, in particular its directional dependence (anisotropy), are even more pronounced than in black phosphorus. However, black nitrogen can only exist thanks to the exceptional pressure and temperature conditions under which it is produced in the laboratory. Under normal conditions it dissolves immediately. "Because of this instability, industrial applications are currently not feasible. Nevertheless, nitrogen remains a highly interesting element in materials research. Our study shows by way of example that high pressures and temperatures can produce material structures and properties that researchers previously did not know existed," says Laniel.

Determining structure with particle accelerators

It took truly extreme conditions to produce black nitrogen. The compression pressure was 1.4 million times the pressure of the Earth's atmosphere, and the temperature exceeded 4,000 degrees Celsius. To find out how atoms arrange themselves under these conditions, the Bayreuth scientists cooperated with the German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg and the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at the Argonne National Laboratory in the USA. Here, X-rays generated by particle acceleration were fired at the compressed samples. "We were surprised and intrigued by the measurement data suddenly providing us with a structure characteristic of black phosphorus. Further experiments and calculations have since confirmed this finding. This means there is no doubt about it: nitrogen is, in fact, not an exceptional element, but follows the same golden rule of the periodic table as carbon and oxygen do," says Laniel, who came to the University of Bayreuth in 2019 as an Alexander von Humboldt Foundation research fellow.