New textile could keep you cool in the heat, warm in the cold

Same fabric can perform both functions

Advertisement

Imagine a single garment that could adapt to changing weather conditions, keeping its wearer cool in the heat of midday but warm when an evening storm blows in. In addition to wearing it outdoors, such clothing could also be worn indoors, drastically reducing the need for air conditioning or heat. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces have made a strong, comfortable fabric that heats and cools skin, with no energy input.

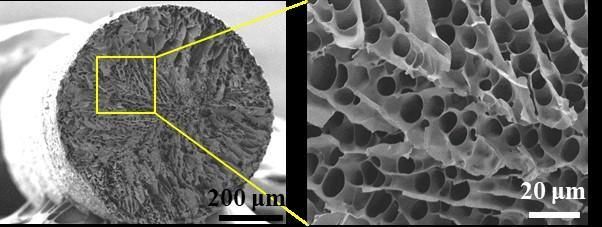

A microstructured fiber (left) contains pores (right) that can be filled with a phase-changing material that absorbs and releases thermal energy.

ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, DOI: 10.1021/acsami.0c02300

"Smart textiles" that can warm or cool the wearer are nothing new, but typically, the same fabric cannot perform both functions. These textiles have other drawbacks, as well -- they can be bulky, heavy, fragile and expensive. Many need an external power source. Guangming Tao and colleagues wanted to develop a more practical textile for personal thermal management that could overcome all of these limitations.

The researchers freeze-spun silk and chitosan, a material from the hard outer skeleton of shellfish, into colored fibers with porous microstructures. They filled the pores with polyethylene glycol (PEG), a phase-changing polymer that absorbs and releases thermal energy. Then, they coated the threads with polydimethylsiloxane to keep the liquid PEG from leaking out. The resulting fibers were strong, flexible and water-repellent. To test the fibers, the researchers wove them into a patch of fabric that they put into a polyester glove. When a person wearing the glove placed their hand in a hot chamber (122 F), the solid PEG absorbed heat from the environment, melting into a liquid and cooling the skin under the patch. Then, when the gloved hand moved to a cold (50 F) chamber, the PEG solidified, releasing heat and warming the skin. The process for making the fabric is compatible with the existing textile industry and could be scaled up for mass production, the researchers say.