Using corkscrew lasers to separate mirror molecules

Innovative approach could deepen insight into the mysterious handedness of life

Many of the molecular building blocks of life have two versions that are mirror images of one another, known as enantiomers. Although seemingly identical, the two enantiomers can have completely different chemical behaviour – a fact that has major implications in our day-to-day lives. For example, while one version of the organic compound carvone smells like spearmint, the mirror form smells like caraway seed. In pharmacology and drug design it can be essential to be able to distinguish between the two enantiomers and separate them if necessary, since the consequences can be life-changing. For instance, while one enantiomer of beta blockers selectively targets the heart, the other acts only on the cell membranes of the eye.

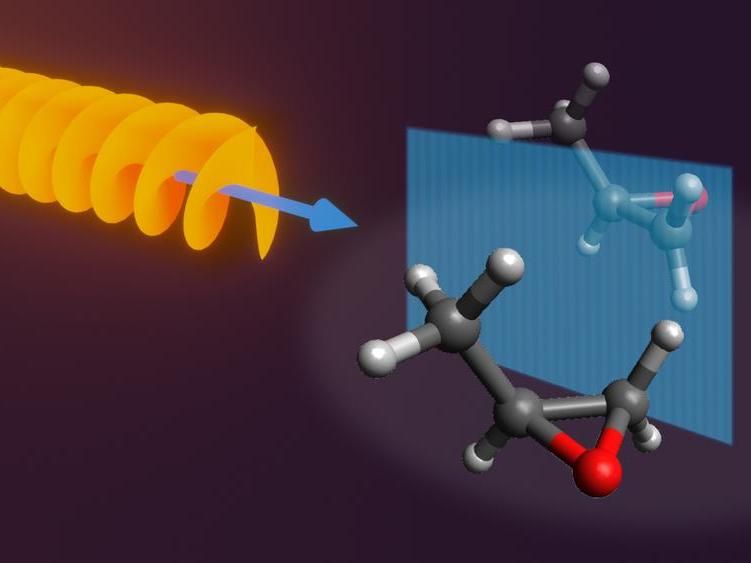

The new approach proposes to combine a corkscrew-like laser pulse with an electric field to spatially separate mirror molecules.

DESY, Andrey Yachmenev

Now, a research team from DESY, Universität Hamburg and University College London have come up with an innovative new approach to separate mirror molecules and in doing so introduced a new theoretical framework to understand the phenomenon. The work is published in the journal Physical Review Letters. Molecules that exist in mirror versions of each other are called chiral after the Ancient Greek word for hand, referring to the fact that the right and left hand are mirror versions of each other. For so-far unknown reasons, life often favours one version: While proteins are almost always left-handed, sugars are usually right-handed.

“Traditionally, chiral analysis has been restricted to liquids but we are seeing a growing rise in gas-phase methods as they offer far greater sensitivity,” says DESY scientist Andrey Yachmenev, lead author of the study. “The ability to cool gases down close to absolute zero affords us better control of our sample, and this in turn can be exploited to efficiently separate the enantiomers and produce higher yields of one enantiomer instead of the other.”

At the heart of their approach is a specially designed laser-setup composed of an optical centrifuge, a corkscrew-shaped laser pulse that can spin molecules incredibly fast, over a trillion times per second. When combined with an additional electric field, the entire setup becomes chiral and the two enantiomers behave differently, displaying unique quantum dynamics.

“The interaction of the laser field with a chiral molecule creates what we call a field-induced diastereomer,” explains co-author Emil Zak from DESY. Diastereomers are different configurations of the same compound that are not mirror versions of each other. The distinct characteristics of diastereomers can be utilised to separate the enantiomers in space. “Importantly, our approach is controllable and we can increase the production of one enantiomer over the other by simply changing the length of time that the molecules spend interacting with the laser-field,” adds co-author Alec Owens from University College London.

The scheme has been computationally demonstrated on the prototypical chiral molecule propylene oxide (C3H6O), which was incidentally also the first complex organic chiral molecule to be detected in interstellar space. Efforts are now underway to perform experiments at DESY and capitalise on the electrostatic deflection techniques pioneered in the Controlled Molecule Imaging group led by Jochen Küpper at the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science CFEL, a joint institution of DESY, Max Planck Society, and Universität Hamburg.

“Manipulating chiral molecules in the gas-phase is undergoing a period of exciting development, both for practical applications used in industry, and for providing new insights into what is a very fundamental aspect of nature,” says Yachmenev. “The origin of chirality and life’s handedness is one of the great mysteries, but we are gradually getting closer to a deeper and more complete understanding.”

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.