How light steers electrons in metals

Advertisement

ETH physicists have measured how electrons in so-called transition metals get redistributed within a fraction of an optical oscillation cycle. They observed the electrons getting concentrated around the metal atoms within less than a femtosecond. This regrouping might influence important macroscopic properties, such as electrical conductivity, magnetization or optical characteristics. The work therefore suggests a route to controlling these properties on extremely fast time scales.

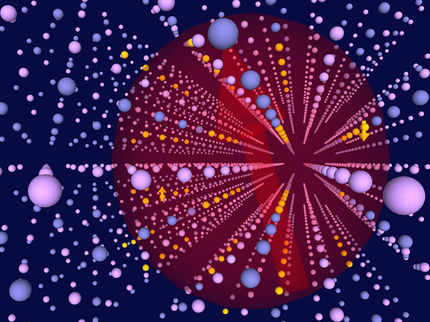

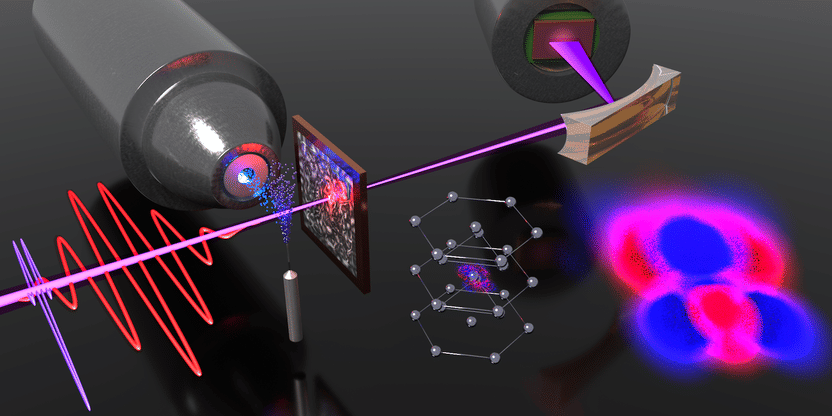

Illustration of the setup and the interaction of a short laser pulse (red oscillating line) with the lattice of titanium atoms (centre, lower half of figure). The red and blue structures represent the redistribution of the electron density in the vicinity of a titanium atom; a close-up is shown on the bottom right.

ETH Zurich/D-PHYS Ultrafast Laser Physics group

The distribution of electrons in transition metals, which represent a large part of the periodic table of chemical elements, is responsible for many of their interesting properties used in applications. The magnetic properties of some of the members of this group of materials are, for example, exploited for data storage, whereas others exhibit excellent electrical conductivity. Transition metals also have a decisive role for novel materials with more exotic behaviour that results from strong interactions between the electrons. Such materials are promising candidates for a wide range of future applications.

In their experiment, whose results they report in a paper published in Nature Physics, Mikhail Volkov and colleagues in the Ultrafast Laser Physics group of Prof. Ursula Keller exposed thin foils of the transition metals titanium and zirconium to short laser pulses. They observed the redistribution of the electrons by recording the resulting changes in optical properties of the metals in the extreme ultraviolet (XUV) domain. In order to be able to follow the induced changes with sufficient temporal resolution, XUV pulses with a duration of only few hundred attoseconds (10-18 s) were employed in the measurement. By comparing the experimental results with theoretical models, developed by the group of Prof. Angel Rubio at the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter in Hamburg, the researchers established that the change unfolding in less than a femtosecond (10-15 s) is due to a modification of the electron localization in the vicinity of the metal atoms. The theory also predicts that in transition metals with more strongly filled outer electron shells an opposite motion — that is, a delocalization of the electrons — is to be expected.

Ultrafast control of material properties

The electron distribution defines the microscopic electric fields inside a material, which do not only hold a solid together but also to a large extent determine its macroscopic properties. By changing the distribution of electrons, one can thus steer the characteristics of a material as well. The experiment of Volkov et al. demonstrates that this is possible on time scales that are considerably shorter than the oscillation cycle of visible light (around two femtoseconds). Even more important is the finding that the time scales are much shorter than the so-called thermalization time, which is the time within which the electrons would wash out the effects of an external control of the electron distribution through collisions between themselves and with the crystal lattice.

Initial surprise

Initially, it came as a surprise that the laser pulse would lead to an increased electron localization in titanium and zirconium. A general trend in nature is that if bound electrons are provided with more energy, they will become less localized. The theoretical analysis, which supports the experimental observations, showed that the increased localization of the electron density is a net effect resulting from the stronger filling of the characteristic partially filled d-orbitals of the transition-metal atoms. For transition metals with d-orbitals that are already more than half filled (that is, elements more towards the right in the periodic table), the net effect is to the opposite and corresponds to a delocalization of the electronic density.

Towards faster electronic components

While the result now reported is of fundamental nature, the experiments demonstrate the possibility of a very fast modification of material properties. Such modulations are used in electronics and opto-electronics for the processing of electronic signals or the transmission of data. While present components process signal streams with frequencies in the gigahertz (109 Hz) range, the results of Volkov and co-workers indicate the possibility of signal processing at petahertz frequencies (1015 Hz). These rather fundamental findings might therefore inform the development of the next generations of ever-faster components, and through this indirectly find their way into our daily life.