Weyl fermions discovered in another class of materials

A particular kind of elementary particle, the Weyl fermions, were first discovered a few years ago. Their specialty: They move through a material in a well ordered manner that practically never lets them collide with each other and is thus very energy efficient. This implies intriguing possibilities for the electronics of the future. Up to now, Weyl fermions had only been found in certain non-magnetic materials. Now however, for the very first time, scientists at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have experimentally proven their existence in another type of material: a paramagnet with intrinsic slow magnetic fluctuations. This finding also shows that it is possible to manipulate the Weyl fermions with small magnetic fields. It thus opens further possibilities to use them in spintronics, a promising development in electronics for novel computer technology.

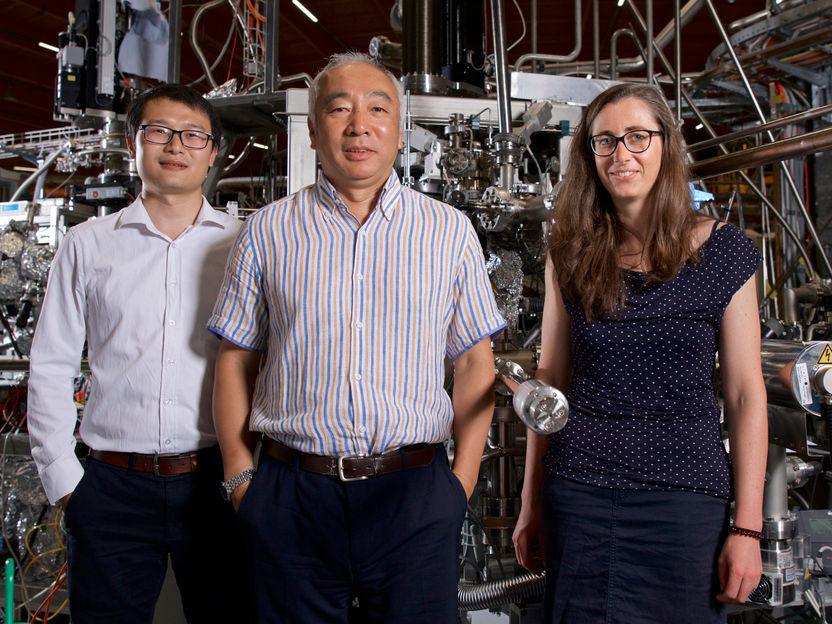

The three PSI researchers Junzhang Ma, Ming Shi and Jasmin Jandke (from left to right) at the Swiss Light Source SLS, where they succeeded in proving the existence of Weyl fermions in paramagnetic material.

Paul Scherrer Institut/Markus Fischer

Amongst the approaches that could pave the way to energy efficient electronics of the future, Weyl fermions could play an intriguing role. Found experimentally only inside materials as so-called quasi-particles, they behave like particles which have no mass. Predicted theoretically already in 1929 by the mathematician Hermann Weyl, their experimental discovery by scientists amongst other at PSI only came in 2015. So far, Weyl fermions had only been observed in certain non-magnetic materials. Now however, a team of scientists at PSI together with researchers in the USA, China, Germany and Austria also found them in a specific paramagnetic material. This discovery could bring a potential usage of Weyl fermions in future computer technology one step closer.

Searching for slow magnetic fluctuations

“The difficult part,” says Junzhang Ma, postdoctoral researcher at PSI and first author of the new study, “was to identify a suitable magnetic material in which to look for these Weyl fermions.” For years, although the accepted theoretical assumption had been that in certain magnetic materials Weyl fermions could exist by themselves, experimental proof of this was still missing despite considerable effort from several research groups worldwide. The team of scientists at PSI then had the idea to turn their attention to a specific group of magnetic materials: paramagnets with slow magnetic fluctuations.

“In specific paramagnetic materials, these intrinsic magnetic fluctuations could suffice to create a pair of Weyl fermions,” says Ming Shi, who is a professor in the same research group as Ma: the Spectroscopy of Novel Materials Group. “But we understood that the fluctuations had to be slow enough in order for the Weyl fermions to appear. From this point on, identifying which material could have sufficiently slow magnetic fluctuations became our primary challenge.”

Since the characteristic time of the magnetic fluctuations is not a feature that can be checked in a work of reference for every material, it took the researchers some time and effort to find a suitable material for their experiment. Model analysis in theoretical physics also done at PSI helped them in identifying a promising candidate with slow magnetic fluctuations: the material with the chemical notation EuCd2As2: Europium-Cadmium-Arsenic. And indeed, in this paramagnetic material, the scientists were able to experimentally prove Weyl fermions.

Measurements with Muons and X-rays

The scientists used two of PSIs large research facilities for their experiments: First, they employed the Swiss Muon Source SμS to measure and better characterise the magnetic fluctuations of their material. Subsequently, they visualized the Weyl fermions with an x-ray spectroscopy method at the Swiss Light Source SLS.

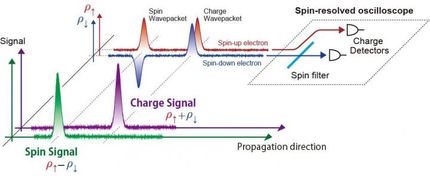

“What we have proven here is that Weyl fermions can exist in a wider range of materials than previously thought”, says Junzhang Ma. The scientists’ research thus significantly broadens the range of materials considered viable in the search for materials suitable for the electronics of the future. Within an area of development called spintronics, Weyl fermions could be used to transport information with much higher efficiency than that achieved by electrons in today’s technology.

Original publication

"Spin fluctuation induced Weyl semimetal state in the paramagnetic phase of EuCd2As2"; J.-Z. Ma, S. M. Nie, C. J. Yi, J. Jandke, T. Shang, M. Y. Yao, M. Naamneh, L. Q. Yan, Y. Sun, A. Chikina, V. N. Strocov, M. Medarde, M. Song, Y.-M. Xiong, G. Xu, W. Wulfhekel, J. Mesot, M. Reticcioli, C. Franchini, C. Mudry, M. Müller, Y. G. Shi, T. Qian, H. Ding, M. Shi; Science Advances 12. Juli 2019 (online)