Researchers take two steps toward green fuel

Two-Step Saccharification of Rice Straw Using Solid Acid Catalysts

Advertisement

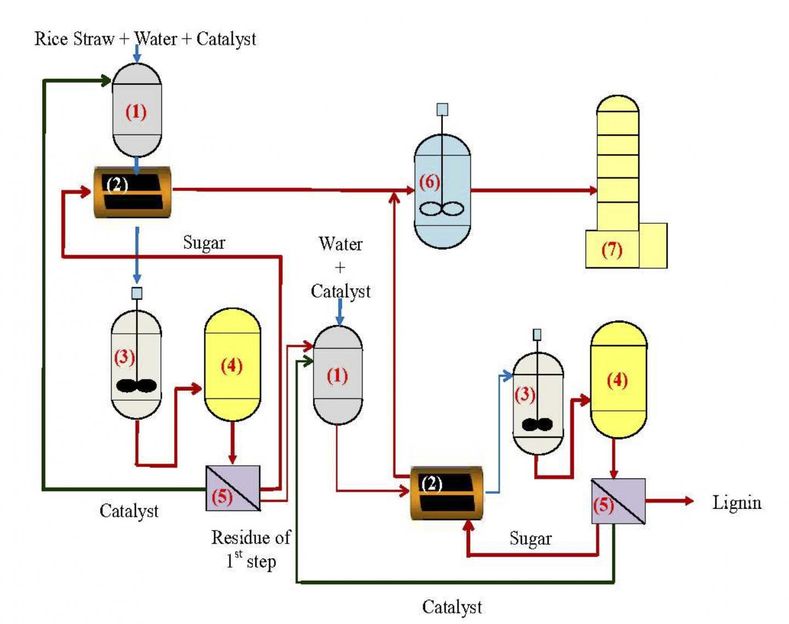

An international collaboration led by scientists at Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT) , Japan, has developed a two-step method to more efficiently break down carbohydrates into their single sugar components, a critical process in producing green fuel.

Researchers designed two-step process to break down rice straws into sugars for fuel.

Figure adapted from Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019 58 (14), 5686-5697. Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society

The breakdown process is called saccharification. The single sugar components produced, called monosaccharides, can be fermented into bioethanol or biobutanol, alcohols that can be used as fuel.

"For a long time, considerable attention has been focused on the utilization of homogenous acids and enzymes for saccharification," said Eika W. Qian, paper author and professor in the Graduate School of Bio-Applications and Systems Engineering at the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology in Japan. "Enzymatic saccharification is seen to be a reasonable prospect since it offers the potential for higher yields, lower energy costs, and it's more environmentally friendly."

The use of enzymes to break down the carbohydrates could actually be hindered, especially in the practical biomass such as rice straw. A byproduct of rice harvest, rice straw consists of three complicated carbohydrates: starch, hemicellulose and cellulose. Enzymes cannot approach hemicellulose or cellulose, due to their cell wall structure and surface area, among other characteristics. They must be pre-treated to become receptive to the enzymatic activity, which can be costly.

One answer to the cost and inefficiency of enzymes is the use of solid acid catalysts, which are acids that cause chemical reactions without dissolving and becoming a permanent part of the reaction. They're particularly appealing because they can be recovered after saccharification and reused.

Still, it's not as easy as swapping the enzymes for the acids, according to Qian, as the carbohydrates are non-uniform. Hemicellulose and starch degrade at 180 degrees Celsius and below, and if the resulting components are heated further, the sugars produced discompose and are converted to other byproducts. On the other hand, degradation of cellulose only happens at temperatures of 200 degrees Celsius and above.

That's why, in order to maximize the resulting yield of sugar from rice straw, the researchers developed a two-step process - one step for the hemicellulose and another for the cellulose. The first step requires a gentle solid acid at low temperatures (150 degrees Celsius and below), while the second step consists of harsher conditions, with a stronger solid acid and higher temperatures (210 degrees Celsius and above).

Overall, the two-step process not only proved effective, it produced about 30 percent more sugars than traditional one-step processes.

"We are now looking for a partner to evaluate the feasibility of our two-step saccharification process in rice straw and other various materials such as wheat straw and corn stoke etc. in a pilot unit," Qian said. "Our ultimate goal is to commercialize our process to manufacture monosaccharides from this type of material in the future."