A combination of agrochemicals shortens the life of bees

A nonlethal dose of insecticide clothianidin can reduce honeybees' life span by half

Advertisement

A new study by Brazilian biologists suggests that the effect of pesticides on bees could be worse than previously thought. Even when used at a level considered nonlethal, an insecticide curtailed the lives of bees by up to 50%. The researchers also found that a fungicide deemed safe for bees altered the behavior of workers and made them lethargic, potentially jeopardizing the survival of the entire colony.

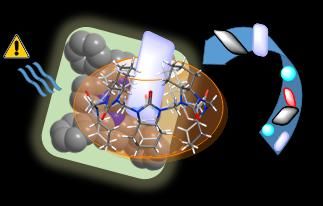

A nonlethal dose of insecticide clothianidin can reduce honeybees' life span by half; once combined with the fungicide pyraclostrobin, it alters the behavior of worker bees to the point of endangering the whole colony.

Credit Cristiano Menezes (left) and Catalina Angel (right).

The results of the study are published in Scientific Reports. The principal investigator was Elaine Cristina Mathias da Silva Zacarin, a professor at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) in Sorocaba, São Paulo State, Brazil. Researchers affiliated with São Paulo State University (UNESP) and the University of São Paulo's Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ-USP) also took part in the study.

The São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP supported the research under the aegis of the Thematic Project "Bee-agriculture interactions: perspectives on sustainable use", for which the principal investigator is Osmar Malaspina, a professor at UNESP in Rio Claro campus. Funding was also provided by the Brazilian government via CAPES, the higher education research council, and by the Sorocaba Beekeepers' Cooperative (COAPIS).

It is a well-known fact that several bee species are disappearing worldwide. The phenomenon has been observed since 2000 in Europe and the United States and since at least 2005 in Brazil.

In Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil's southernmost state, the loss of some 5,000 colonies, corresponding to 400 million bees, was reported between December 2018 and January 2019.

One of the most widely affected species is Apis mellifera, the Western honeybee, which is of European origin and the source of most commercially available honey.

Hundreds of wild native Brazilian species may also be affected in the natural environment. The economic impact is estimated to be huge, as most agricultural crops depend on pollination by bees. All kinds of edible fruit are just one clear example.

The reason for this sudden mass disappearance is also well known: it is the indiscriminate and improper application of agrochemicals, such as insecticides, fungicides, herbicides and acaricides. Bees are contaminated when out of the hive and bring the toxic chemicals back with them on their return. Inside the nest, the chemicals are ingested by larvae, shortening their lives and impairing the functioning of the entire colony.

"Soybean, corn and sugarcane monocultures in Brazil depend on the intensive use of insecticide. Bee colonies are contaminated, for example, if farmers fail to comply with the recommended minimum safety margin of 250 m between a crop and the surrounding forest when spraying their fields. There are people who spray right up to the edge of the forest," Malaspina said.

"In Europe and the US, bee colonies die off gradually. Between one and five months may elapse between the first report of bee mortality and the destruction of the colony. It's different in Brazil. Colonies vanish here in just 24 or 48 hours. No disease can kill a whole colony in 24 hours. Only insecticide can do that."

Malaspina recalled that the insecticides, fungicides, herbicides and acaricides used in Brazil contain hundreds of active ingredients. "It's impossible to test the action of each one in the laboratory. The money isn't available," he said.

A study was conducted between 2014 and 2017 by Colmeia Viva, an initiative of the agrochemical industry association (SINDIVEG), to identify active ingredients that might be associated with bee mortality in the 44 products most widely sprayed on crops in São Paulo State.

The researchers collected material in 40 municipalities across the state. Working with beekeepers, farmers and the agrochemical industry, they came up with a set of recommended actions to protect apiaries and enforce best practices in agriculture, as well as the minimum safety margin when applying agrochemicals already mentioned.

Risks of combined exposure

According to the scientists, the beneficial effects of Colmeia Viva may begin to appear. While 5,000 colonies disappeared in Rio Grande do Sul, losses were lower in Santa Catarina and Paraná, the other two states in the southern region, and lower still in São Paulo State.

"However, that doesn't mean São Paulo's bees are no longer at risk from agrochemicals," Zacarin said. "We're beginning to carry out tests to measure the effects on honeybees of combined exposure to insecticide and fungicide. We've already discovered that a specific fungicide doesn't harm bee colonies when sprayed on its own but becomes toxic to bees when associated with a certain insecticide. It doesn't kill them as insecticide does, but it alters their behavior and puts colonies at risk."

The active ingredients investigated were clothianidin, an insecticide used to control pests that attack cotton, dry beans, corn and soybeans, and pyraclostrobin, a fungicide applied to the leaves of most grain and fruit crops, as well as legumes and vegetables.

"We tested agrochemicals for toxicity in bee larvae and the environment, using relevant criteria in the sense that we were looking for realistic levels such as those found residually in flower pollen," Zacarin said.

This is an important point. Any heavily sprayed agrochemical decimates bee colonies almost immediately. The researchers are studying the subtle effects of spraying over the medium to long term. "What we want to find out is how the residual action of agrochemicals applied even at very low levels affects bees," Zacarin explained.

Change in behavior

The tests were conducted in a laboratory to avoid environmental contamination. Larvae of A. mellifera were taken from healthy colonies, separated into groups, placed in grafting cells, and fed between the third and sixth day after transfer on a diet of royal jelly and sugar blended with a tiny dose of one or the other agrochemical. The dose was a few nanograms (billionths of a gram).

The control group's diet contained no agrochemicals. The second and third groups' diets were contaminated either with the insecticide clothianidin or with the fungicide pyraclostrobin. The insecticide and fungicide were both added to the diet of the fourth group of larvae.

"When larvae are six days old, they become pupae and begin metamorphosis, emerging as adult workers," Zacarin said. "In the wild, the life of a worker bee lasts 45 days on average. When they're confined to the lab, these bees' lives are shorter, but the lives of the specimens we fed a diet contaminated with very small amounts of the insecticide clothianidin were drastically curtailed, by as much as 50%."

No effect was observed on the life span of the workers that emerged from larvae fed a diet contaminated solely by the fungicide pyraclostrobin.

"Based on this result alone, we might assume that a very small dose of the fungicide is harmless. Unfortunately, that's not the case," Zacarin said.

No bees died in the larval or pupal stage, but the behavior of the adult workers changed. They were sluggish compared with the control group.

"Young workers make daily inspections of the hive and so they have to travel a certain distance and move about a lot in the colony. We found that bees contaminated with the fungicide alone, or with both the fungicide and insecticide combined, covered a much smaller distance and moved much more slowly," Zacarin said.

If a substantial proportion of worker bees in an actual hive were affected to the same extent, this alteration in behavior would impair the functioning of the entire colony and could be one of the reasons for the mass extinctions observed.

The researchers do not yet know exactly how the fungicide acts to change the bees' behavior. "Our hypothesis is that when pyraclostrobin is associated with an insecticide, it diminishes the bee's energy metabolism. Further studies are in progress to elucidate this mechanism," Zacarin said.