The cycling of poisonous chemicals from the past

Monsoon remobilizes phased-out chemicals stored in South Asian soils

persistent organic pollutants are toxic chemicals that cannot decompose in nature, or only do so very slowly, and are harmful to the environment. Through accumulation along food chains they also have significant negative effects on human health. Nowadays, many of them are banned. Traces of those compounds can still be found in soils, oceans, vegetation and air globally. An international team, led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, has now found out that persistent organic pollutants, stored for decades in South Asian soils, can be re-mobilized by the monsoon and volatilize into the air. The research, published recently in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, contributes to the understanding of the large scale distribution and fate of chemical pollution.

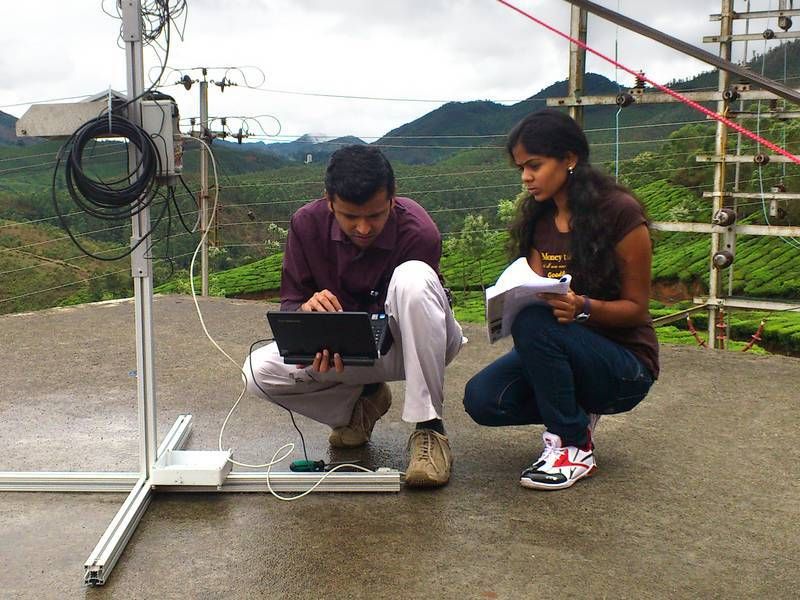

Sachin S Gunthe (left) and Akila Muthalagu during the measurements in India.

Gerhard Lammel

Chemicals such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are included in the list of the Stockholm Convention, an international treaty aimed at protecting human health and the environment from persistent organic pollutants (POPs). The production and use of these substances is thus either banned or highly restricted.

One key region where POPs have been heavily used as agricultural pesticides in the past is South Asia. The region is thus considered a hot spot. Until now studies on environmental exposure of the Indian subcontinent have been mostly limited to urban areas, while rural inland regions were scarcely addressed.

In order to understand the interaction between the monsoon air masses moving from the Indian Ocean to the Asian continent and the POPs concentrations in continental background soils, the scientists performed measurements in the Western Ghats mountains. “It was very important but equally difficult for us to find a suitable location over India to test our hypothesis that a drop in the air´s pollutant concentration at the onset of the summer monsoon mobilizes chemicals stored in soils. Munnar in the Western Ghats mountains combined a perfect geographical position with unique meteorological conditions,” says Sachin S. Gunthe, researcher at the Indian Institute of Technology in Chennai.

The analyses of soil and air suggest that the arrival of the summer monsoon triggers net volatilization or enhances the on-going re-volatilization of the now banned chemicals HCH and PCBs from soils in southern India. The study results showed that the re-volatilization from soils pollutes the air progressively more as the monsoon propagates northward and eastward across the subcontinent during June and July.

“Both the field measurements and modeling results of this study indicate a mechanism of pollutant cycling over the Indian subcontinent that has thus far been overlooked,” says Gerhard Lammel, Research Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry and principal investigator of the study. “A part of the pollutant burden in Indian soils is pulled out by the monsoon once per year and undergoes large-scale re-distribution.”

Getting to the bottom of the dynamics of soil contamination and exchange with the overlying air is crucial for assessing the spatio-temporal scales of the distribution and fate of chemical pollution in the region and globally. The investigation of the potential of organic chemicals to re-volatilize from land and sea surfaces is key for understanding the exposure of the environment and of humans, and hence the risk assessment of man-made chemicals in general.

Original publication

"Re-volatilisation of soil accumulated pollutants triggered by the summer monsoon in India"; Gerhard Lammel, Céline Degrendele, Sachin S. Gunthe, Qing Mu, Akila Muthalagu, Ondřej Audy, Chelackal V. Biju, Petr Kukučka, Marie D. Mulder, Mega Octaviani, Petra Příbylová, Pourya Shahpoury, Irene Stemmler, and Aswathy E. Valsan; Atmos. Chem. Phys.; 2018, 18, 11031-11040

Original publication

"Re-volatilisation of soil accumulated pollutants triggered by the summer monsoon in India"; Gerhard Lammel, Céline Degrendele, Sachin S. Gunthe, Qing Mu, Akila Muthalagu, Ondřej Audy, Chelackal V. Biju, Petr Kukučka, Marie D. Mulder, Mega Octaviani, Petra Příbylová, Pourya Shahpoury, Irene Stemmler, and Aswathy E. Valsan; Atmos. Chem. Phys.; 2018, 18, 11031-11040

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.