'Dancing' holes in droplets submerged in water-ethanol mixtures

Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University have observed the formation of holes that move by themselves in droplets of ionic liquids (IL) sitting inside water-ethanol mixtures. This curious, complex phenomenon is driven by an interplay between how ionic liquids dissolve, and how the boundary around the droplet fluctuates. Self-driven motion is a key feature of active matter, materials that use ambient energy to self-propel, with potential applications to drug delivery and nano-machine propulsion.

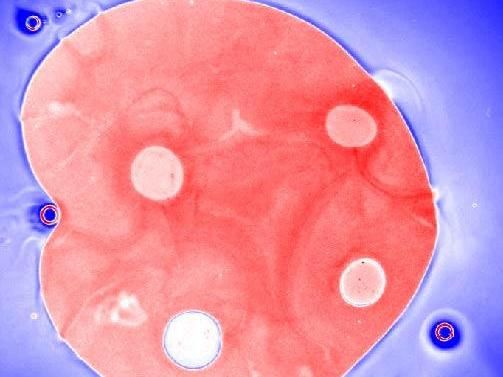

This is a droplet of ionic liquid (Red) with active holes (white holes) in a water-ethanol solvent (Blue). The holes propel themselves inside the IL droplet.

Rei Kurita

Most people are familiar with how things mix or dissolve. For example, we know that water and ethanol mix very well at room temperature; take alcoholic beverages. How well they mix depends on the environment the mixture is in, like temperature and pressure.

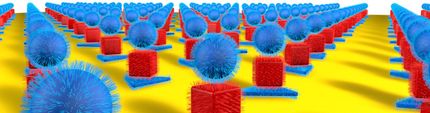

However, dissolution takes a complex turn when we add another component. A team led by Associate Professor Rei Kurita, Department of Physics, Tokyo Metropolitan University, were studying how an ionic liquid (IL) dissolved in a mixture of water and ethanol. Ionic liquids are liquids composed entirely of ions in ambient conditions; properties like their resistance to drying and ability to dissolve otherwise difficult materials have led to their being referred to as a "solvent of the future", with a focus on how they might play a role in industrial processes e.g. battery production, pharmaceuticals, and recycling.

The team placed a small droplet of IL at the bottom of a mixture of ethanol and water. With the temperature and particular ratio of ethanol to water they used, they expected a boundary or interface to form between the IL and the water-ethanol above it, and for the two to mix gradually. Yet, what they saw was startling: over time, holes emerged inside the IL droplet, and the holes could propel themselves inside the droplet.

They found that this curious phenomenon was the result of how the composition of the water-ethanol mixture naturally fluctuated around the interface. The conditions were such that the mixture is close to a critical point, where small variations in composition can have major consequences. In this case, they were enough to locally promote mixing of the IL into the water-ethanol mixture; the unique way in which ILs interact with water led to even further local changes in composition, leading to a positive feedback loop, or instability. The effect was so drastic that they led to variations in the surface tension, driving the surface to become spontaneously bumpy, form holes, and generate the large flows required to move them around. These holes have been dubbed active holes.

Their discovery paves the way for a broad new class of synthetic active matter, materials that can spontaneously take energy from its surroundings and convert it into motion. With possible applications to drug delivery and propulsion at the nanometer scale, this new phenomenon might inspire investigations into novel industrial uses as well as further accelerate academic interest in active phenomena.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.