Repellent research: Ship coatings to reduce fuel, energy costs

It can repel water, oil, alcohol and even peanut butter. And it might save the U.S. Navy millions of dollars in ship fuel costs, reduce the amount of energy that vessels consume and improve operational efficiency.

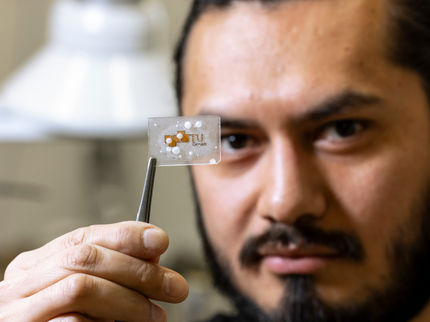

Mathew Boban, a graduate student research assistant at the University of Michigan, pours hexadecane oil onto a glass slide covered with an omniphobic coating. The petroleum-based, highly viscous oil slides easily off the glass. The Office of Naval Research is sponsoring efforts to see how omniphobic coatings might reduce friction drag--resistance created by the movement of a hull through water - on ships, submarines and unmanned underwater vessels.

Robert Coelius, Michigan Engineering Communications & Marketing

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) is sponsoring work by Dr. Anish Tuteja, an associate professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Michigan, to develop a new type of "omniphobic" coating. This chemical coating is clear, durable, can be applied to numerous surfaces and sheds just about any liquid.

Of particular interest to the Navy is how omniphobic coatings can reduce friction drag--resistance created by the movement of a hull through water--on ships, submarines and unmanned underwater vessels.

Compare friction drag to jogging through a swimming pool. Because of the water's resistance, each stride is more difficult and requires more energy and effort.

"A significant percentage of a ship's fuel consumption [up to 80 percent at lower speeds and 40-50 percent at higher speeds] goes toward maintaining its speed and overcoming friction drag," said Dr. Ki-Han Kim, a program officer in ONR's Sea Warfare and Weapons Department. "If we could find a way to drastically reduce friction drag, vessels would consume less fuel or battery power, and enjoy a greater range of operations."

Tuteja's omniphobic coating could be a solution. Picture two ships sailing at the same speed--one dealing with friction drag and the other covered in a coating that causes water to bead up and slide off the hull easily. The coated vessel theoretically would guzzle less fuel because it doesn't have to fight as much water resistance while maintaining speed.

While repellent coatings aren't new, it's hard to create one that resists most liquids and is tough enough to stick to various surfaces for long periods of time. Take a Teflon-coated pan, for example. Water will bead up and roll off the pan, while cooking oil will spread everywhere.

"Researchers may take a very durable polymer matrix and a very repellent filler and mix them," said Tuteja. "But this doesn't necessarily yield a durable, repellent coating. Different polymers and fillers have different miscibilities [the ability of two substances to mix together]. Simply combining the most durable individual constituents doesn't yield the most durable composite coating."

To engineer their innovative coating, Tuteja and his research team studied vast computer databases of known chemical substances. They then entered complex mathematical equations, based on each substance's molecular properties, to predict how any two would behave when blended. After analyzing hundreds of combinations, researchers found the right mix.

The molecular marriage was a hit during laboratory tests. The rubber-like combo can be sprayed, brushed, dipped or spin-coated onto numerous surfaces, and it binds tightly. The coating also can withstand scratching, denting and other hazards of daily use. And the way the molecules separate makes the coating optically clear.

Besides reducing friction drag, Tuteja envisions other Navy uses for the omniphobic coating--including protecting high-value equipment like sensors, radars and antennas from weather.

In addition to omniphobic coatings to lessen friction drag, ONR is sponsoring other types of coating research to prevent corrosion on both ships and aircraft and fight biofouling (the buildup of barnacles on hulls). Similar coatings can also prevent ice from forming on ships operating in cold regions, or make ice removal much easier than conventional methods like scraping.

Tuteja's team is conducting further tests on the omniphobic coating, but they plan to have it ready for small-scale military and civilian use within the next couple of years.