Thin engineered material perfectly redirects and reflects sound

Metamaterial device controls transmission and reflection of acoustic waves

metamaterials researchers at Duke University have demonstrated the design and construction of a thin material that can control the redirection and reflection of sound waves with almost perfect efficiency.

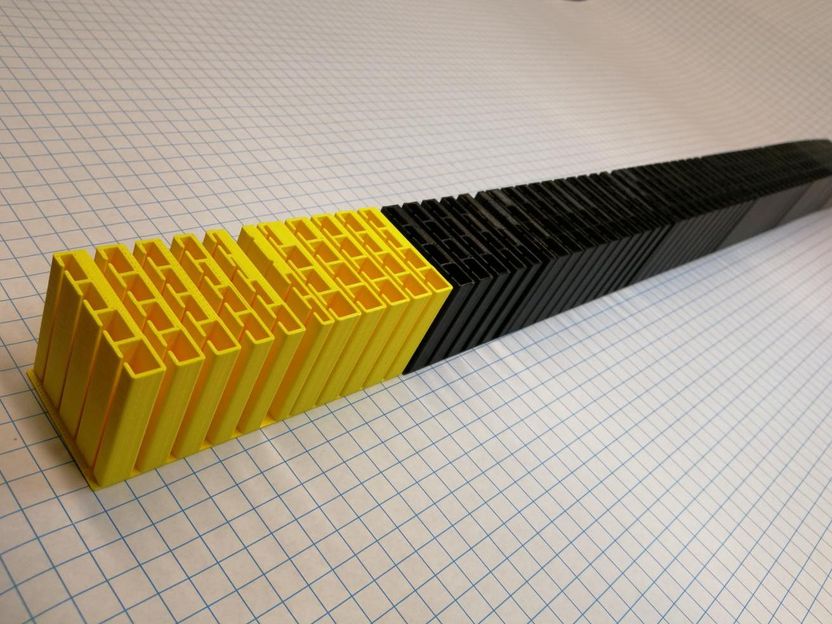

This metamaterial surface has been engineered to perfectly and simultaneously control the transmission and reflection of incoming sound waves.

Junfei Li

While many theoretical approaches to engineer such a device have been proposed, they have struggled to simultaneously control both the transmission and reflection of sound in exactly the desired manner, and none have been experimentally demonstrated.

The new design is the first to demonstrate complete, near-perfect control of sound waves and is quickly and easily fabricated using 3-D printers.

"Controlling the transmission and reflection of sound waves this way was a theoretical concept that did not have a path to implementation -- nobody knew how to design a practical structure using these ideas," said Steve Cummer, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Duke. "We solved both of those problems. Not only did we figure out a way to design such a device, we could also make one and test it. And lo and behold, it actually works."

The new design uses a class of materials called metamaterials -- artificial materials that manipulate waves like light and sound through their structure rather than their chemistry. For example, while this particular metamaterial is made out of 3-D printed plastic, it's not the properties of the plastic that are important -- it's the shapes of the device's features that allow it to manipulate sound waves.

The metamaterial is made of a series of rows of four hollow columns. Each column is nearly one-half of an inch on a side with a narrow opening cut down the middle of one side, making it look somewhat like the world's deepest Ethernet port. While the device demonstrated in the paper is 1.6 inches tall and nearly 3.5 feet long, its height and width are irrelevant -- it could theoretically stretch on forever in either direction.

The researchers control how the device manipulates sound through the width of the channels between each row of columns and the size of the cavity inside each individual column. Some columns are wide open while others are nearly closed off.

To understand why, think of someone blowing air across the top of a glass bottle -- the pitch the bottle makes depends on the amount of liquid left inside the bottle. Similarly, each column resonates at a different frequency depending on how much of it is filled in with plastic.

As a sound wave travels through the device, each cavity resonates at its prescribed frequency. This vibration not only affects the speed of the sound wave but interacts with its neighboring cavities to tame both transmission and reflection.

"Previous devices could shape and redirect sound waves by changing the speed of different sections of the wave front, but there was always unwanted scattering," said Junfei Li, a doctoral student in Cummer's laboratory and first author of the paper. "You have to control both the phase and amplitude of both the transmission and reflection of the wave to approach perfect efficiencies."

To make matters more complicated, the vibrating columns not only interact with the sound wave, but also with their surrounding columns. Li needed to write an 'evolutionary computer optimization program,' to work through all the design permutations.

The researchers feed the program the boundary conditions needed on each side of the material to dictate how they want the outgoing and reflected waves to behave. After trying a random set of design solutions, the program mixes various combinations of the best solutions, introduces random "mutations," and then runs the numbers again. After many iterations, the program eventually "evolves" a set of design parameters that provide the desired result.

In the paper, Cummer, Li and colleagues demonstrate that one such set of solutions can redirect a sound wave coming straight at the metamaterial to a sharp 60-degree outgoing angle with an efficiency of 96 percent. Previous devices would have been lucky to achieve 60 percent efficiencies under such conditions. While this particular setup was designed to control a sound wave at 3,000 Hertz -- a very high pitch not dissimilar to getting a "ringing in your ears" -- the metamaterials could be scaled to affect almost any wavelength of sound.

The researchers and their collaborators are next planning to transfer these ideas to the manipulation of sound waves in water for applications such as sonar, although there aren't any ideas for applications in air. At least not yet.

"When talking about waves, I often fall back on the analogue of an optical lens," said Cummer. "If you tried to make really thin eyeglasses using the same approaches that these sorts of devices have been using for sound, they would stink. This demonstration now allows us to manipulate sound waves extremely accurately, like a lens for sound that would be way better than previously possible."