C’mon electrons, let’s do the twist!

Twisting electrons can tell right-handed and left-handed molecules apart.

Identifying right-handed and left-handed molecules is a crucial step for many applications in chemistry and pharmaceutics. An international research team (CELIA-CNRS/INRS/Berlin Max Born Institute/SOLEIL) has now presented a new original and very sensitive method. The researchers use laser pulses of extremely short duration to excite electrons in molecules into twisting motion, the direction of which reveals the molecules’ handedness.

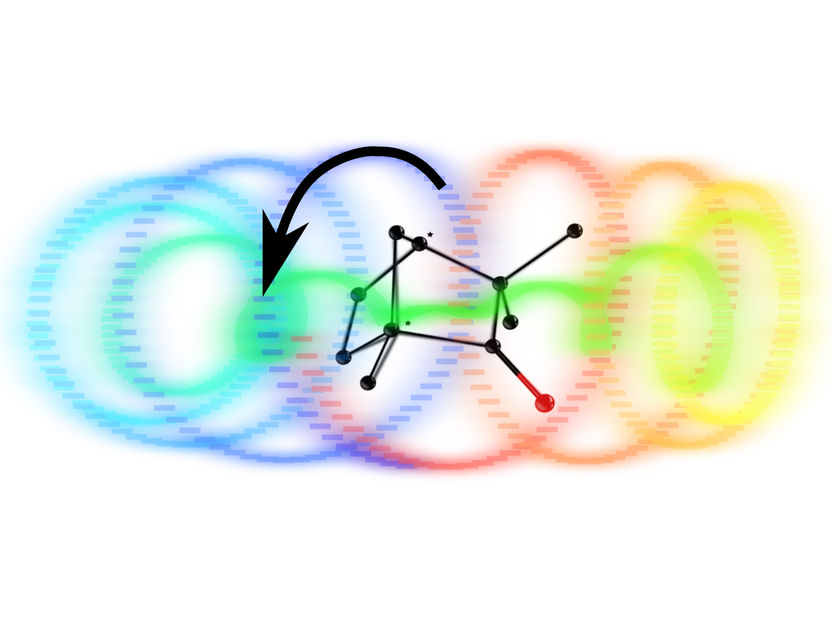

Following excitation by an ultra-short circularly polarised laser pulse, electrons follow a right or left helix depending on the handedness of the molecular structure they reside in.

Samuel Beaulieu

Are you right handed or left handed? No, we aren’t asking you, dear reader; we are asking your molecules. It goes without saying that, depending on which hand you use, your fingers will wrap either one way or the other around an object when you grip it. It so happens that this handedness, or ‘chirality’, is also very important in the world of molecules. In fact, we can argue that a molecule’s handedness is far more important than yours: some substances will be either toxic or beneficial depending on which “mirror-twin” is present. Certain medicines must therefore contain exclusively the right-handed or the left-handed twin.

The problem lies in identifying and separating right-handed from left-handed molecules, which behave exactly the same unless they interact with another chiral object. An international research team has now presented a new method that is extremely sensitive at determining the chirality of molecules.

We have known that molecules can be chiral since the 19th century. Perhaps the most famous example is DNA, whose structure resembles a right-handed corkscrew. Conventionally, chirality is determined using so-called circularly polarised light, whose electromagnetic fields rotate either clockwise or anticlockwise, forming a right or left “corkscrew”, with the axis along the direction of the light ray. This chiral light is absorbed differently by molecules of opposite handedness. This effect, however, is small because the wavelength of light is much longer than the size of a molecule: the light’s corkscrew is too big to sense the molecule’s chiral structure efficiently.

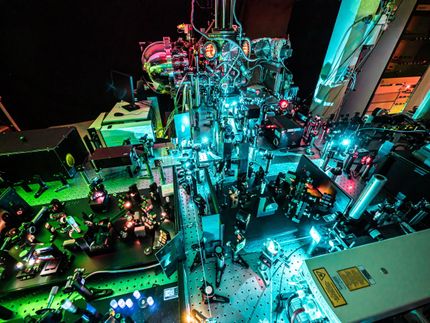

The new method, however, greatly amplifies the chiral signal. “The trick is to fire a very short, circularly polarized laser pulse at the molecules,” says Olga Smirnova from the Max Born Institute. This pulse is only some tenths of a trillionth of a second long and transfers energy to the electrons in the molecule, exciting them into helical motion. The electrons’ motion naturally follows a right or left helix in time depending on the handedness of the molecular structure they reside in.

Their motion can now be probed by a second laser pulse. This pulse also has to be short to catch the direction of electron motion and have enough photon energy to knock the excited electrons out of the molecule. Depending on whether they were moving clockwise or anticlockwise, the electrons will fly out of the molecule along or opposite to the direction of the laser ray.

This lets the experimentalists of CELIA to determine the chirality of the molecules very efficiently, with a signal 1000 times stronger than with the most commonly used method. What’s more, it could allow one to initiate chiral chemical reactions and follow them in time. It comes down to applying very short laser pulses with just the right carrier frequency. The technology is a culmination of basic research in physics and has only been available since recently. It could prove extremely useful in other fields where chirality plays an important role, such as chemical and pharmaceutical research.

Having succeeded in identifying the chirality of molecules with their new method, the researchers are now thinking already of developing a method for laser separation of right- and left-handed molecules.