First metallic nanoparticles resistant to extreme heat

Just as a gecko sheds its tail, metal-alloy particles endure 850 degrees Celsius by ditching weaker components, researchers report in Nature Materials

Advertisement

A University of Pittsburgh team overcame a major hurdle plaguing the development of nanomaterials such as those that could lead to more efficient catalysts used to produce hydrogen and render car exhaust less toxic. The researchers reported Nov. 29 in Nature Materials the first demonstration of high-temperature stability in metallic nanoparticles, the vaunted next-generation materials hampered by a vulnerability to extreme heat.

Götz Veser, an associate professor and CNG Faculty Fellow of chemical and petroleum engineering in Pitt's Swanson School of Engineering, and Anmin Cao, the paper's lead author and a postdoctoral researcher in Veser's lab, created metal-alloy particles in the range of 4 nanometers that can withstand temperatures of more than 850 degrees Celsius, at least 250 degrees more than typical metallic nanoparticles. Forged from the catalytic metals platinum and rhodium, the highly reactive particles work by dumping their heat-susceptible components as temperatures rise, a quality Cao likened to a gecko shedding its tail in self-defense.

"The natural instability of particles at this scale is an obstacle for many applications, from sensors to fuel production," Veser said. "The amazing potential of nanoparticles to open up completely new fields and allow for dramatically more efficient processes has been shown in laboratory applications, but very little of it has translated to real life because of such issues as heat sensitivity. For us to reap the benefits of nanoparticles, they must withstand the harsh conditions of actual use."

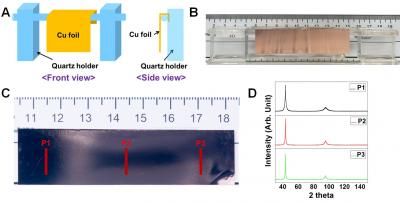

Veser and Cao present an original approach to stabilizing metallic catalysts smaller than 5 nanometers. Materials within this size range boast a higher surface area and permit near-total particle utilization, allowing for more efficient reactions. But they also fuse together at around 600 degrees Celsius—lower than usual reaction temperatures for many catalytic processes—and become too large. Attempts to stabilize the metals have involved encasing them in heat-resistant nanostructures, but the most promising methods were only demonstrated in the 10- to 15-nanometer range, Cao wrote. Veser himself has designed oxide-based nanostructures that stabilized particles as small as 10 nanometers.

For the research in Nature Materials, he and Cao blended platinum and rhodium, which has a high melting point. They tested the alloy via a methane combustion reaction and found that the composite was not only a highly reactive catalyst, but that the particles maintained an average size of 4.3 nanometers, even during extended exposure to 850-degree heat. In fact, small amounts of 4-nanometer particles remained after the temperature topped 950 degrees Celsius, although the majority had ballooned to eight-times that size.

Veser and Cao were surprised to find that the alloy did not simply endure the heat. It instead sacrificed the low-tolerance platinum then reconstituted itself as a rhodium-rich catalyst to finish the reaction. At around 700 degrees Celsius, the platinum-rhodium alloy began to melt. The platinum "bled" from the particle and formed larger particles with other errant platinum, leaving the more durable alloyed particles to weather on. Veser and Cao predicted that this self-stabilization would occur for all metal catalysts alloyed with a second, more durable metal.

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Sensor technology

Sensor technology has revolutionized the chemical industry by providing accurate, timely and reliable data across a wide range of processes. From monitoring critical parameters in production lines to early detection of potential malfunctions or hazards, sensors are the silent sentinels that ensure quality, efficiency and safety.

Topic world Sensor technology

Sensor technology has revolutionized the chemical industry by providing accurate, timely and reliable data across a wide range of processes. From monitoring critical parameters in production lines to early detection of potential malfunctions or hazards, sensors are the silent sentinels that ensure quality, efficiency and safety.