UCI scientists discover ozone-boosting chemical reaction

Newfound chemistry should be added to atmospheric models, researchers say

Burning of fossil fuels pumps chemicals into the air that react on surfaces such as buildings and roads to create photochemical smog-forming chlorine atoms, UC Irvine scientists report in a new study.

Under extreme circumstances, this previously unknown chemistry could account for up to 40 parts per billion of ozone – nearly half of California's legal limit on outdoor air pollution. This reaction is not included in computer models used to predict air pollution levels and the effectiveness of ozone control strategies that can cost billions of dollars.

Ozone can cause coughing, throat irritation, chest pain and shortness of breath. Exposure to it has been linked to asthma, bronchitis, cardiopulmonary problems and premature death.

"Realistically, this phenomenon probably accounts for much less than 40 parts per billion, but our results show it could be significant. We should be monitoring it and incorporating it into atmospheric models," said Barbara Finlayson-Pitts, Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and lead author of the study. "We still don't really understand important elements of the atmosphere's chemistry."

Study results appear the week of July 20 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

When fossil fuels burn, compounds called nitrogen oxides are generated. Previously, scientists believed these would be eliminated from the atmosphere upon contact with surfaces.

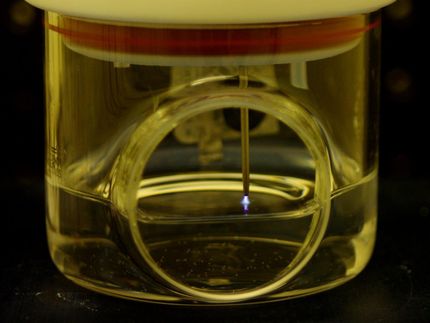

But UCI scientists discovered that when nitrogen oxides combine with hydrochloric acid from airborne sea salt on buildings, roads and other particles in the air, highly reactive chlorine atoms are created that speed up smog formation.

Hydrochloric acid also is found indoors in cleaning products. When it interacts with nitrogen oxides from appliances such as gas stoves, chlorine compounds form that cause unusual chemistry and contribute to corrosion indoors.

The study was undertaken by scientists involved with AirUCI, an Environmental Molecular Sciences Institute funded by the National Science Foundation. UCI's Jonathan Raff conducted experiments; Bosiljka Njegic and Benny Gerber made theoretical predictions; and Wayne Chang and Donald Dabdub did the modeling. Mark Gordon of Iowa State University also helped with theory.

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.