New 'molecular movie' reveals ultrafast chemistry in motion

X-ray laser measures atomic-scale details of how ring-shaped gas molecule breaks open, unravels

Advertisement

Scientists for the first time tracked ultrafast structural changes, captured in quadrillionths-of-a-second steps, as ring-shaped gas molecules burst open and unraveled. Ring-shaped molecules are abundant in biochemistry and also form the basis for many drug compounds. The study points the way to a wide range of real-time X-ray studies of gas-based chemical reactions that are vital to biological processes.

Researchers working at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory compiled the full sequence of steps in this basic ring-opening reaction into computerized animations that provide a "molecular movie" of the structural changes.

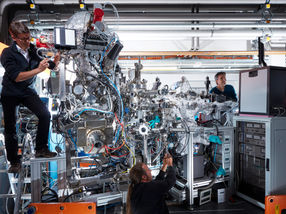

Conducted at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, the pioneering study marks an important milestone in precisely tracking how gas-phase molecules transform during chemical reactions on the scale of femtoseconds.

"This fulfills a promise of LCLS: Before your eyes, a chemical reaction is occurring that has never been seen before in this way," said Mike Minitti, a SLAC scientist who led the experiment in collaboration with Peter Weber at Brown University.

"LCLS is a game-changer in giving us the ability to probe this and other reactions in record-fast timescales," Minitti said, "down to the motion of individual atoms." The same method can be used to study more complex molecules and chemistry.

he free-floating molecules in a gas, when studied with the uniquely bright X-rays at LCLS, can provide a very clear view of structural changes because gas molecules are less likely to be tangled up with one another or otherwise obstructed, he added. "Until now, learning anything meaningful about such rapid molecular changes in a gas using other X-ray sources was very limited, at best."

New Views of Chemistry in Action

The study focused on the gas form of 1,3-cyclohexadiene (CHD), a small, ring-shaped organic molecule derived from pine oil. Ring-shaped molecules play key roles in many biological and chemical processes that are driven by the formation and breaking of chemical bonds. The experiment tracked how the ringed molecule unfurls after a bond between two of its atoms is broken, transforming into a nearly linear molecule called hexatriene.

"There had been a long-standing question of how this molecule actually opens up," Minitti said. "The atoms can take different paths and directions. Tracking this ultimately shows how chemical reactions are truly progressing, and will likely lead to improvements in theories and models."

The Making of a Molecular Movie

In the experiment, researchers excited CHD vapor with ultrafast ultraviolet laser pulses to begin the ring-opening reaction. Then they fired LCLS X-ray laser pulses at different time intervals to measure how the molecules changed their shape.

Researchers compiled and sorted over 100,000 strobe-like measurements of scattered X-rays. Then, they matched these measurements to computer simulations that show the most likely ways the molecule unravels in the first 200 quadrillionths of a second after it opens. The simulations, performed by team member Adam Kirrander at the University of Edinburgh, show the changing motion and position of its atoms.

Each interval in the animations represents 25 quadrillionths of a second - about 1.3 trillion times faster than the typical 30-frames-per-second rate used to display TV shows.

A gas sample was considered ideal for this study because interference from any neighboring CHD molecules would be minimized, making it easier to identify and track the transformation of individual molecules. The LCLS X-ray pulses were like cue balls in a game of billiards, scattering off the electrons of the molecules and onto a position-sensitive detector that projected the locations of the atoms within the molecules.

Original publication

M.P. Minitti, et al., Physical Review Letters, 2015.